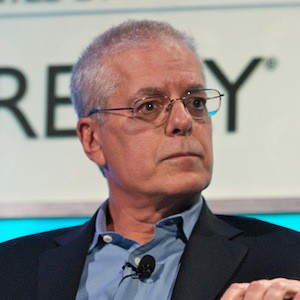

Martin Nisenholtz: We are here at 15 West 52nd Street on March 14th, my wife’s birthday, with Gordon Crovitz, the ex publisher of the Wall Street Journal, the ex chief digital officer for Dow Jones, and currently the founding co CEO, I believe, of Press+. Gordon, why don’t I start. Why don’t we talk about your first time. That is, when did you first realize that electronic publishing, digital technologies would affect newspaper publishing or journalism?

Gordon Crovitz: I remember that moment very well. I was based in Hong Kong in the mid ’90s, ’95 or ’96, running a part of Dow Jones that had electronic publishing, but the old fashioned kind. I came from a three or four hour meeting. The question was, “How long would it take for developers to be able to use non English language characters on the green screens that Dow Jones was then offering to traders and others for real time information.”

I was back in New York for a meeting and Neil Budde, who was later the founding editor of the Wall Street Journal’s website, showed a group of us off his laptop this unbelievable product, which was the first iteration of the Wall Street Journal’s website built on HTML.

He explained how he had done it and he explained this HTML. It was the most amazing thing I’d ever heard. We saw the demo and I asked him at the end of the meeting. I said, “That was fantastic, but how many months is it going to take to develop that? Time to produce it? That [inaudible 00:02:04] looks fantastic, but really how long is it going to take?” He looked at me said, “I don’t think you understand. It’s live now.”

The contrast between electronic publishing in the old days, the pre Internet days and the Internet couldn’t have been more stark to me.

Martin: From there, you did what?

Gordon: From there, I came back to New York and helped sell that part of Dow Jones, the old fashioned terminal part of Dow Jones. It’s called Telerate. Then became responsible for what at Dow Jones was still called electronic publishing as opposed to print publishing. That included everything from real time news and what became Factiva, the news retrieval system, and the Wall Street Journal’s website and the other websites of the company.

One more historical point I have here, I don’t think it’s going to be very visible, but what I have here is an advertisement for the Wall Street Journal from 1899. The headlines says, “There are 180,000 shareholders in the various newly formed industrial companies. Are you one of them?”

It suggests that if you are an investor or hope to be one, you should read the Wall Street Journal. The interesting thing is the graphic. What you can see here is a broker. This is Trinity Church in the background. It’s Wall Street. You see a ticker machine, which is a Dow Jones ticker similar, by the way, to the ticker patented by Thomas Edison, [inaudible 00:03:40] .

This is a Dow Jones ticker and the message to readers is, “You can get your news from the same source that your broker is getting his news from.” Of course, he’s getting it in real time and you’re going to get it once a day.

In fact, the history of the Wall Street Journal is Dow and Jones had all this extra copy lying around after their doing their real time news. They said, “Let’s put them into a daily newspaper for consumers, not just brokers.”

The whole history of the Wall Street Journal was how do you get more information to more people more quickly? There’d been an effort within Dow Jones to create a consumer version of the Wall Street Journal pre HTML. That’s why Neil Budde was working on this project. There was a thinking machine, one of those giant computers in Princeton New Jersey offices.

HTML, the beginning of the Internet, and the Wall Street Journal’s website was a radical achievement of that goal of trying to get news and information to people electronically and not just on a once a day basis.

Martin: Yes, I remember that proprietary service. I don’t remember the name of it, but it was like AOL…

Gordon: It was. It was originally called Dow Jones News/Retrieval.

Martin: But there was a lighter version…

Gordon: It was licensed to AOL and Prodigy and some others, Dow Jones online.

John Huey: Dow Jones is retrievable going all the way back into the ’70s, right? So dial up, telephone system.

Gordon: It was, and when John and I were in Brussels in the early ’80s, I don’t know if John knows this. I memorized the code to get access to Dow Jones News/Retrieval. On Saturdays, I would come to the office and I would read newspapers because that was the only way to get newspapers that were not Belgian or maybe French in Brussels at that time in the early ’80s. I backslashed back to…This time, people were going to Berkeley and places like that to get master’s degrees in information and library science to be able to use systems like Dow Jones News/Retrieval. The news junkies in the ’80s, there was Dow Jones News/Retrieval, there was Nexus, which was still pretty new. Those required private networks and a lot of knowledge to be able to use them.

John: How long did your progress go on with developing the website and the web business before you came to the debate of free versus paid?

Gordon: I can’t take credit for that decision because I was still running the very high charging real-time financial news, part of the business in Asia. That decision was pretty much locked down by Peter Kann, the then CEO of the company.

John: At the beginning.

Gordon: At the very beginning. There was never, as I recall and as people say, never really much of a debate. The debate was really how much do we charge? It was never is this going to be free? I think one reason for that is that unlike most newspaper companies, Dow Jones, since its very beginning, since even before the Wall Street Journal, was selling news electronically to subscribers. The whole revenue base was subscriptions for what’s now the Dow Jones News Wire and the other services.

Of course, we were charging for the print version of the Wall Street Journal, so I think it was natural to [charge]…

John: You always had two streams of content income, in other words.

Gordon: Correct.

John: From the beginning.

Martin: And they never had a significant classified advertising business like most newspapers did that needed [protection] …

Gordon: Exactly because it was not a metro paper, there was not a lot of classified advertisement, very little. I used to keep a running chart on revenue volatility comparing the Wall Street Journal, largely advertising based and the other revenue streams, which were almost all subscription based. One was as beautiful flattish line that grew over time, but not very volatile. That was a subscription part. Advertising looked like EKG of a dying person, up and down.

By several years after the launch, it became clear that the most valuable revenue stream, the Wall Street Journal franchise, was digital subscription revenue. Very high renewal rates, extremely high profit margin.

Martin: One of the interviews we did was with Larry Kramer, and it was interesting. He said that he prayed every night that you guys would continue to maintain your pay wall so that he could build his business. How do you react to that?

Gordon: Well, of course, in many ways, he was right. One of the reasons that I approached Larry to ask him when CBC MarketWatch was independent company, to ask him what he thought the future of CBS MarketWatch might be, and would he be interested in being purchased by Dow Jones? One of the reasons for that discussion was, and this is going to be very hard to believe now, but at this time just 2003 or 4, the Wall Street Journal’s website was sold out in terms of online advertising at a very high CPM.

Martin: Not hard to believe.

Gordon: Forrester Research was projecting 80 percent increases in revenue for publishers like that, far into the future. I didn’t want to give up the subscription revenue. There was no technology, at that time, to get the best of both worlds. There was no opportunity to charge in a different way. It was an old fashioned pay wall, which meant, to get virtually any Wall Street Journal content, you had to be a subscriber. That did suppress the number of visitors and suppressed advertising inventory. There are better ways to charge now, that allow you to get around that. But at that time, one of the reasons DOW Jones bought Market Watch was vastly to expand the number of page views and to sell those ads as part of a Wall Street Journal network, which included the opportunity to increase prices on the MarketWatch site.

Larry was right. He was able to grow Market Watch into quite a large audience. I would say it also served a somewhat different audience than The Wall Street Journal, because it was very focused on individual investors, whereas The Wall Street Journal is more of a broad business brand. So individual investors were either going to Market Watch or Yahoo Finance. But I was glad to be able to reward him with an acquisition for his work.

Martin: One of the themes that keeps coming up, over and over again, is this notion of culture, inside of the large journalistic institutions. And the idea that they just, in their native cultures, simply couldn’t adapt. Did you create a separate division and if so, was it for that reason? In other words, talk a little bit about the culture, back in the mid ’90s, and how that evolved over time.

Gordon: There certainly were cultural differences, at that time, between the print folks and what we would now call digital folks. We then called electronic folks. The Wall Street Journal had one big advantage, which was, as part of DOW Jones, it had always been electronic publishing. So there was in the DNA some focus on electronic publishing that didn’t exist at most or maybe any other newspapers. That meant, especially in the news department, which was for most of that period, run by Paul Steiger, a deep understanding of how news flowed through different ways. A lot of Wall Street Journal reporters had had to file DOW Jones ers. Real time, to the ticker.

John: Oh, listen. When I went to work for The Wall Street Journal in 1975, you spent two weeks out of every four, working real time news all day long. It was a wire service. There were no news moments. It was, when you got the news, you reported it. That very much presaged what became the online news mentality later. It was an easy adaptation. We were all trained to do that. That was something that didn’t happen to the rest of the news business for 20 years.

Gordon: Right. So that was a huge advantage. It was especially visible in the news department where, organizationally, for most of that period, until 2006, there was a structural separation, between print and electronic publishing. But especially in the news department, especially with Paul Steiger running it, he really ran it as an integrated group. Even though, during that period, the editors of the online journal reported to me, but in fact they worked so closely with Paul, it was hard to say exactly where they reported. And it was never an issue. That was very different from the experience elsewhere. I can remember taking the head of Time Inc. Digital to lunch of breakfast, every 18 months, the new on.

It was about every 18 months there was a new one. I developed a little analogy for that person. I said, “Within Time Inc. you are a German prince with this great role and a castle with a moat around it and hot, burning oil you can dump on people if they try to get in your way. The problem is, you’re surrounded by other German princes, the brand managers for all those different brands. They’ve got hot oil and sharks in the moat. You’re never going to get anything done. “

Dow Jones is different. It’s so small. We’re like the grand duchy of Luxembourg. We have castles, but the moats don’t really work anymore. The oil is tepid. It’s easier to get stuff done, easier to work across different silos and different organizational structures. In part because it was smaller and in part because of this… Electronic publishing was already in the DNA.

Martin: Let’s talk about the difference. What you’ve just addressed is a kind of sense that there was an alternate distribution, an electronic distribution possibility. But when Neal showed you the website, obviously there’s a great creative difference between publishing on the web and publishing even in the traditional electronic form. Yet most newspapers mostly repurposed their print or even wire copy into the web, while guys like Yahoo and others were developing applications on top of the content. Can you talk about that? Do you think that was the right approach back then? Was it the only possible approach for a business like The Wall Street Journal, or for that matter, any other journalist organization?

Gordon: There are brand expectations that, at the end of the day, are very influential on business strategy. The brand expectations for a Wall Street Journal reader, in print and online, are kind of the same. It’s delivered in a different form, but it they still want the business news delivered in a highly credible, authoritative, thought out way. They want some element of, “Don’t waste my time.” The print Wall Street Journal, the “What’s News?” column in the pre Internet era. Those of us who are old enough to remember what it was like to get the print Wall Street Journal in the morning. The “What’s News?” column solved two enormous problems for millions of people. One problem was, “What happened that I needed to know about?”

The other problem was, “Do I really know about something else?” The “What’s News?” column achieved, for business people, for many years, the value of delivering to that person, “Here’s what you need to know about…and by the way, if it’s not in the ‘What’s News?’ column, don’t worry about it.”

John: And it was in order of relative importance. That order of importance, along with The New York Times, page one frontings on Reuters every night, became the two central ways to know what was important. That was when hierarchy mattered.

Gordon: Imagine what an easy life it was for news consumers then. You didn’t have that many sources. Some editor told you what was really important. If you were gone to the office you didn’t have to worry that your boss knew something you didn’t know and vice versa, by the way.

Paul Sagan: Then that changed.

Gordon: And then that changed, and online for the Wall Street Journal there was still that sense of this is what’s really important. This is of less importance. And, of course, as technology allowed…somebody recently used the phrase, “the nuggetization of content.” So each individual story or part of a story or a Twitter reference to a story, all of those pieces of content flow in such different ways now. And for many people Twitter is the new version of the print, “What’s News?” column. This is what my friends are reading. I’d better read it also. So I think traditional brands had a difficult time with that transition to real time news, and a difficult time with that transition to letting consumers determine how they wanted to consume the news. That’s a very different experience from the more traditional approach to publishing.

John: And by the way, the guy who was the most legendary for setting the order of that, “What’s News?” column every day now sets the order on the Bloomberg home screen every day. Gordon, you’ve got to back up a little bit. Dow Jones always kept one eye on Reuters for various, for your wholesale business and your news service business, so you were always watching Reuters and their slow encroachment in the U.S. and your global competitor.

Do you…I’m not sure where you were when Reuters made the decision to sell content to Yahoo, which then created Yahoo Finance and Yahoo News off that, but we’ve identified that as a fairly seminal moment in this progression. Do you recall that and what you thought?

Gordon: Absolutely. It was a seminal moment. Reuters, a fascinating company had gone from being a general news service very similar to the AP to becoming a Forex trading platform and developing enormous revenues in the real time market, and that’s even by that period, which was the mid ’90s, Reuters was already generating almost all of its revenues and earnings from the real time financial services market. What consumers think of as the Reuters brand kind of like the AP brand, tiny part of the business. So for Reuters it was a great opportunity to extend their brand, particularly in North America, and because it was not a significant revenue stream for them at that time, not charging or charging very little was not a big corporate risk to them. It did lead…in my case it contributed to some very awkward discussions with companies like Microsoft, and AOL, and others where…

I recall one in particular where we were going down to renew a licensing agreement, I think this was with Microsoft. We wanted to renew a licensing agreement where Microsoft had licensed Dow Jones content. They didn’t have access to the Wall Street Journal brand because Wall Street Journal content was only available to subscribers, but it was version of that called, “Dow Jones Online.”

And we walked in expecting a renewal of the seven figures that Microsoft was paying to the Wall Street Journal, and the topic instead became how much was I going to pay Microsoft to distribute Dow Jones News. Think of all the exposure you could get. And I asked them to repeat their notion, and they really wanted me to pay them. We didn’t agree to do that. That did not seem like a good business model to me.

And then next thing I knew was a jump ball between Reuters and Bloomberg, and as I recall at the time Bloomberg paid Microsoft to distribute some news. I think Bloomberg has since rethought that strategy but it was a very odd time in terms of publishers establishing value and different publishers had different strategies.

And in the case of Reuters I think they would say it was a smart move for them to develop a lot more awareness of their brand in the North American market, and they didn’t have much money to lose anyway. So I think it was all part of the creative destruction of traditional business models, and different companies took a different attitude towards how best to deal with it.

Martin: Gordon, I want to just return to this notion of culture and consumer expectation, because I think it’s at the nub of a lot of this stuff. There’s a school of thought that basically says that if folks like you and me and others in the mid ’90s had really pushed much harder to try and transcend those expectations and pushed the brand much more aggressively into a direction that was, call it more sustainable over the long term. We wouldn’t necessarily be in the position we’re in today, whether at Journal or the Times. Essentially, interestingly, the business models have kind of converged.

I have my view of that. I’m not going to proffer it here, but what is your view of that? Were you…do you feel that you were aggressive enough in pushing the culture to do perhaps to get out of its comfort zone and do more than it could have possibly done?

Gordon: I think when you look back you have to say nobody did enough. I mean Yahoo became an old media company within a few years. I take some consolation from that. So I don’t think any of us in traditional media companies did enough. On the other hand, we did quite a lot so if you think about the case of the Wall Street Journal, in retrospect the big question was not so much, “Can we do more digitally?” I think looking back the real question was did we do enough to create different revenue streams?” Because at least the way I see things advertising, generally speaking, print, online, every form, is in a downward trajectory that will continue in terms of being a support for journalism, for newsrooms.

And so the way I would kind of recraft your question is did we do enough to find new revenue streams so that we would not be so dependent on advertising and so that all the companies like Google and others, Facebook, now Twitter, others that are going to get a bigger share of the advertising market because of the way they address the market. Did we do enough to create sustainable revenue models to support that journalism, and there I think we all have to say we didn’t do enough.

Martin: So let me ask that question a different way, because I think culture questions are important. Was it more a question…is the difference between cultures in the old organizations more on the margin, or was the real cultural difference the technology culture? The Valley versus the East Coast would be the easiest way to put it, but just the application versus the content creation and editing?

Gordon: I think, yes…I think the focus that you would expect from a journalistic enterprise on the journalism on the news on telling stories and doing it in media that people are familiar with that was obviously a limiting factor if the contrast to that was using algorithms to create a Twitter to turn that into a news product, which, by the way, I think it is. LinkedIn is a news product now for many people. Facebook, obviously, for many people is a news product. I think it was very hard for traditional publishing companies even to imagine those services. By the way it was hard for the founders of some of those services to imagine what they would become. On the news side I would say generally, and this is true definitely for the Wall Street Journal, there were always ideas bubbling up of new ways to present content using digital technologies.

When Dow Jones acquired Market Watch from Larry Kramer in addition to the page views to sell more ads, the other really attractive feature was the video. I think CBS Market Watch was, I believe, the first of their sites to have video on the home page, and that led to an enormous amount of learning about digital video, and the Wall Street Journal now I think is producing four or five hours of digital news every day.

Paul: Video news.

Gordon: Video news. There’s another part of this cultural question, which I think is also a very important one. I mean I’m not sure people appreciate this. At least in my experience it was the business side of the publishing companies that were more conservative, more change resistant, than the news departments.

Paul: Well, that was the Innovator’s Dilemma. They were the ones protecting the current streams of revenue and profit, right?

Gordon: Absolutely. And they had advertising goals to hit for the year, print subscription revenue goals to hit every year, and even at Dow Jones, which I think was placed in a fortunate position for many reasons, even then it was really a challenge to break down some of those silos until there was just a mass restructuring that followed, a really brutal economic period where the Wall Street Journal as a brand was unprofitable for a couple of years. Being unprofitable for a couple years was liberating. It made it a lot easier to say, “Whatever it is we’re doing now, the presumption shouldn’t be that’s the right way to do it.” And it did lead to a massive reorganization, a restructuring, that fully integrated the revenues and expenses for digital and print and made it just one integrated part. That made it so much easier.

But that took until the mid 2000s, so it was a good decade of trying to avoid cannibalization, of internal friction over the way people operated and what their incentives were, what they were paid to do. The tension for a publicly trade company like Dow Jones was at that time, quarterly earnings versus the longer term shift to more digital less shift, more consumer revenues, less ad revenues.

So all those things were going on at that time, and that is one of the reasons I think it’s hard for traditional companies to be the place where innovation happens.

John: So, Gordon, if Dow Jones had one eye on Reuters, or at least a corner of an eye on Reuters, you also had one eye on the New York Times which had the aspirations of becoming the other national newspaper. And so you’re watching Martin and his colleagues over there launch their website which is free and growing rapidly and becomes huge. What are you thinking in the other camp when that’s happening?

Gordon: Right.

John: And feel free to say what you were thinking even though Martin is sitting right here.

Gordon: [laughs] I’m going to. The other one…

Martin: Well, we had quarterly lunches all during that period…

[pause]

John: So, Gordon, Dow Jones also had one eye open for the New York Times, which had aspirations to become the other national newspaper, and it was taking a radically different approach with its web business, which was to give it away free, and that had great results. It grew rapidly and created a lot of revenue. In the other camp, what were you thinking?

Gordon: I remember taking…Well, we alternated, Martin and I, taking each other to lunch every quarter to I guess was a mix of commiserating and strategizing and exchanging notes. On the digital side, we were happy to tell each other how things were going, whereas I think our print colleagues at that time would’ve really had a hard time doing that. They were established competitors for advertising and other things.

We had a lot of discussions about it and there were two very different business models. We obviously admired the product of the New York Times. I was happy with my revenue streams, which was a mix of ad revenues and subscription revenues. Martin was a happy with his growth.

Eventually, the two models kind of converged, where there’s a freemium approach. There are still a lot of people getting free content with the New York Times and at the Wall Street Journal but a lot of subscribers. I think the New York Times is well on its way now to being where the Wall Street Journal has been for awhile, which is a huge percentage of the profits in those brands coming from digital subscribers.

I think we had a close eye on the New York Times. When you asked me that question though, what flashed before my eyes, which I had forgotten about for many years, was an article in the business section of the New York Times about the Internet being such a great new thing. There was a box, a chart that contrasts the value that the market had established for different brands. In that box was a contrast between thestreet.com and the Wall Street Journal.

The New York Times reporter said correctly, the market had said there was more value in thestreet.com than in the Wall Street Journal. There were a lot of things we kept our eyes on. We had to keep our eyes on the public market, on how things were being valued, on technology.

Certainly, during those quarterly lunches mostly that Martin and I had, we focused on all kinds…mostly the business of what can we do? What can these properties become? What are the revenue streams going to be? How do we try to maintain some value in the kind of journalism that is done at places like the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal? I think that’s a continuing challenge.

Paul: Talk a little bit about the non traditional but established competition that came in as well, so CNN, which was a free but dynamic and…They were used to just doing news when it happened, as opposed to on a printing deadline. Then of course, Yahoo!, which we talked about, and MSN when it went live.

Gordon: Yeah, I think within the Wall Street Journal, I think one of the reactions was reflection again of the brand, of the Wall Street Journal. I remember when Bill Grueskin, who was then the online Journal editor. He had met with a software company that had figured out a way to send not just email alerts, but alerts that would actually pop up on someone’s screen if they happened to be at that website. Bill and his team came up with a great idea of sending news alerts. He’s one of the first company publishers to do that. Bill said, “But we’re going to do with the Wall Street Journal way. We’re going to do maybe three or four alerts a week. It’s going to be something that really matters, so then when somebody sees the alert, they’re going to know it’s something substantial.”

That was a different approach from, I think ABC made a very nice business out of doing news alerts, but it was a lot of news alerts to a more mass audience. The Journal again, because of position it had as being for a different kind of audience, was able to say, “The winner of the NCAA basketball tournament.” That’s not a news alert for the Wall Street Journal, but if Alan Greenspan at that time coughed, maybe that was a news alert for the Journal kind of reader.

We certainly had an eye on other additional publishers now being able to publish very broadly using this new medium, and some would just have Paul like CNN or broader. There was CNN/FM during the time as well which was more of a competitor to a Wall Street Journal or a Market Watcher, Yahoo Finance. There were a lot of competitors and so I think part of the action of the…

Paul: CNBC.

Gordon: And CNBC, of course, of course with whom the Journal had a deep relationship…

John: But first the Journal tried to buy what became CNBC.

Gordon: Well first we were competing. So when I was in Asia, Chris Graves and some others on a shoestring started ABN, Asia Business News, in Singapore. And my recollection which may be through rose-colored glasses, was that we did a good job competing with GE in Asia, and Europe was kind of jump ball, but they downgraded the U.S. and ended up, obviously, acquiring the Dow Jones assets with a long term relationship, but a complex one that did limit to some degree the amount of video that the Wall Street Journal would be doing on its own. And that has also shifted over time.

Martin: As you fast forward, are there any models today, entrepreneurial models mostly, but not so much the traditional ones trying to [inaudible 00:36:00] , that you think are sustainable over the long term? Any examples, companies that might be particularly interesting in business news in particular?

Gordon: Well, I think if the question is what business models are sustaining journalism there days? There are two companies that seem to have a successful model, in particular Bloomberg and Thompson Reuters. They both have very large news organizations but they’re funded off of a different product. They’re funded off of their data products and their workflow products for financial professionals. They’re able to establish and maintain large news departments. They’re doing more and more enterprise journalism of a kind that they never did a decade ago. But they can do it because they’ve got billions of dollars in revenues from people who are using their services for professional reasons.

And by the way they have almost no reliance on advertising revenue. It’s almost all subscription revenues. I don’t think that’s necessarily a model that can be replicated for many other news publishers. But if yourself who’s got a good model, that’s a pretty good model. Now it may be that LinkedIn and Twitter and Facebook develop similar models where they have other revenue streams where the news is a value to their users.

We’ll have to see if that turns out to be a place to sustain [inaudible 00:37:45] . I think though that we’re in sort of a middle period where there are many, many news brands that do have incremental revenue streams that they can bring in to help with that transition away from somewhat reliance on advertising revenue.

Press+, which is the company that Steve Brill and I started a few years ago, was designed to help all kinds of publishers, generate digital subscription revenues, whether it’s the New York Times or McClatchy or Lee Enterprises or Gatehouse which [owns] lot of very small newspapers. Everybody is doing quite well in terms of new revenues from that source.

It’s not enough to replace the advertising revenue that is still declining: print [and] online. But it takes sustainable recurring high profit margin revenue stream that will also help publishers, particularly newspapers, make the transition away from five sections, seven day a week print products to something else in print. Maybe it’s one section every day. Maybe it’s a couple days a week, but otherwise much more digital publishers.

I think we’re in the middle of…well, I don’t know if it’s the middle. We’re in the process of determining what revenues streams will support journalism. I don’t think we’re really in the middle, honestly. I think it’s more the third inning than the fourth or fifth.

John: You mentioned Thomson Reuters and Bloomberg, which, arguably took a good bit of their market share from the path that Dow Jones had been on for a long time, which was proprietary news and data to professional investors. Was there anything about the disruptive nature of digital media coming to Dow Jones that was related to Dow Jones not thriving, ultimately, in that era? Was it a distraction or was that an unrelated event?

Gordon: I think it was a somewhat related event. I think, looking back on the history here, Dow Jones had acquired a company called Telerate, which, in the ’80s and ’90s was a real competitor in the fixed income market, the bond market with the upstart called Bloomberg, and in international markets with Reuters. Telerate ended under a lot of pressure and Dow Jones ended up selling Telerate. My view of what happened is related to this topic, which is that, for several years in the 1990s, the product development within Telerate depended, to a large degree, on the revenues from print advertising. So in good years for the print Wall Street Journal kicking out a lot of profits from the print Wall Street Journal, which at that time was almost all from advertising.

In those years, Telerate would have some elbow room to invest in the product. In tougher years and there’s a cycle at that time and it worked out for years, there was less money for Telerate to invest in product development.

One thing we now know about digital publishing, electronic publishing is, you can’t miss a cycle or two of product development and be competitive. Bloomberg and Reuters had one business that was serving financial professionals with data with a little bit of news. But they were and are data businesses.

As Telerate missed out on some of the product development, its market share fell precipitously. In retrospect, one of the lessons is that it’s very difficult to run a company with multiple revenue streams and different business models without giving each part of the company its own set of resources to invest in what’s required to make it successful.

Paul: John has come up with this metaphor of swimmers and tide. Some of the things in tide were completely … orthogonal. And most were ad related so probably didn’t affect businesses you were in, but they affected the broader category of news, business models. One was Craigslist, clearly orthogonal to the Journal but not to daily newspapers. That one’s a pretty obvious impact, and the other one was paid search though. Search went from search to paid search and today, still takes more than half of all the ad dollars.

Gordon: Absolutely. Look, I would say it’s even broader than that. To question John Wanamaker, the department store magnate of the 19th century, he was asked, “What was the secret to your success?” He said advertising. The following question was, “Gee, how do you know which advertising was worthwhile and which wasn’t?” He said, “I knew half was wasted. I just never knew which half.” Well, digital technology has reduced that uncertainty around the 50 cents to get a dollar’s worth of bang for about a dime. Part of it is search. A larger part of it, I would say, is the ability of corporate marketers to become publishers themselves, to get their brand distributed, their products described in different ways. There’s some advertising, but a bigger and bigger share of corporate marketing now goes to other things, it goes to companies on websites, to…

John: Facebook campaigns.

Gordon: The Facebook account, right, and obviously, to search, which is a highly measurable, highly effective form of advertising. In the case of the Wall Street Journal, I remember comparing the spending by IBM in the Wall Street Journal, which went from tens of millions of dollars in just the Wall Street Journal to well under 10 million dollars for all print advertising. The Wall Street Journal was, I would actually argue, the first traditional publisher, really, to see the effect of digital technology, even before Craigslist happened. The Wall Street Journal’s advertisers were predominantly financial services companies and technology companies.

Marketers at those two companies were the first to see the opportunities of online advertising, and the first to reduce print, which was then also seen in publications like Business Week and Fortune and Forbes, certainly the Wall Street Journal. And to move more of that spending online, some of which the traditional brands got, but it was trading analog dollars for digital quarters, maybe.

John: Yeah, the advertising page is in the business magazine category, between 2001 and I think, 2005, they dropped something like 10,000 pages. It was just a shocking.

Gordon: Peter Kann got a letter from a reader in about 2000, something like that. And the letter read, “Dear Mr. Kann, You owe me a new dog. I trained my dog to pick up the print Wall Street Journal and bring it to my desk, and Monday’s newspaper was so thick and heavy the dog had a heart attack.” [laughs] So there was a time when the Wall Street Journal, like a lot of print publications, was just chock full [crosstalk] .

[pause]

Paul: Gordon had one more story.

Gordon: I think it’s relevant to this question of cultural differences within companies and trying to grapple with business models. There was a meeting in early 2000s where the tension between the analog part of the company and the digital part of the company were made very clear. It was a proposal from folks on the print side of “The Wall Street Journal” to offer access to “The Wall Street Journal”‘s website to all print subscribers on renewal for free.

On the digital side, we were highly offended by this notion because we had spent years trying to establish value for the digital part. You couldn’t get access without being a paying subscriber.

But from the point of view of the print folks, they were trying to keep their ABC number at a level that they were told it needed to be to support the advertising. From their point of view, it made all the sense in the world to give something away if it was going to improve renewal rates.

There was a meeting scheduled. All the different concerned people came to a meeting, as you do at a big established company. I don’t think I ever did this at any other meeting. It’s kind of smart alecky. If anybody had ever done it to me, I would have been highly annoyed.

I had a prop for the meeting. It was a giant conference room table. I put in the middle of the conference room table a toaster. For young people seeing this, a toaster was like a convection oven, but just for slices of toast. I put in the middle of the table a toaster.

At that time, banks would give toasters to people if they opened an account. You’d get a toaster as a premium, as a giveaway for something else. I put a toaster in the middle of the table. People gathered around the room. We started the meeting, and somebody said, “What’s that toaster doing here?”

I said at that meeting, “What am I doing here? You want my product to be your toaster. You want to give away the digital version of ‘The Wall Street Journal’ after all these years of establishing value? Are you crazy?”

Fast forward to today. It does turn out that the right model is to approach all the print subscribers to a newspaper or a magazine, and have a price increase that gives them digital access and allow them to opt out of digital.

At Press+ we now have hundreds of publishers testing all kinds of things a lot of data. The data all say this is a great model. You increase the price on renewal. You communicate to the print subscriber, “Now you’ve got all digital access on the Web, and mobile, and iPad, and Android, and whatever other versions you might have. It might be a 25 percent increase on the subscription price, but you get digital access also. And by the way, if you don’t want digital, just pay your old print price.” If that’s the offer, 90 percent of the people pay a bit more to get digital access.

If I knew then what I now know, I would’ve had a different attitude toward the toaster. It would have been, “Charge some more for that toaster.” But at that time, it was an example of the kind of tensions within large established companies based on…your position really did depend on where you sat.

Martin: Well, the same thing was true on the advertising side. I mean, people wanted to merchandise the inventory as part of a print buy.

Gordon: Yeah, so there was a lot of value added, meaning I’m not going to charge you more for it.

Paul: That was the term.

Gordon: Oh my God. It was kind of force bundle without value. I think publishers are getting much smarter about value and where the value is. That helps explains why so many publishers now are charging for at least unlimited access to their digital versions. But it sure took a long time for companies to figure all that out.