We are quite aware of all the various alternative models and futurist scenarios that explain how quality general news media might survive. We have also followed all the current techno-rabbits being chased by the advertising industry — video, mobile, etc. Where will all this lead? And what will it mean for journalism? We don’t know. And we don’t really believe anyone else knows either.

Instead of taking on that thankless and impossible task of gazing into our crystal ball, we decided that — after talking to roughly 60 of the most seasoned, invested, thoughtful, powerful, intelligent, humbled, and philosophical people involved with the news industry in its past, present, and future — we would let our interviewees conclude. What follows is a selection of a handful of them who had particularly strong points of view and expressed them frankly.

We begin, not with a crie de coeur from an old-time newsroom hack for salvation, but with a clear articulation of the need for journalism in a digital world from the person whose singular invention did more to enable the collision between news and the Internet than anyone else.

…There’s a need for journalism. People are desperate for it. People are fed up with spam. They’re fed up with just searching, using a web search tool to find a medical article, then realizing only after they have gone to the bottom of the article and followed the advice, and bought the drugs that the whole thing was produced by the same pharmaceutical company, with an extremely slanted view. People are getting so good at presenting stuff which is biased [but appears] as though it is not.

People are fed up with that and journalists have got the skills and the motivation. It’s their job to solve that problem. With all these new genres, don’t expect everything to look like something on the printed page, just translated. Yes, you can think of a blog as an op-ed, but there’s a lot more blogs than there are, were ever, op-ed columns.

The world’s changing shape. Some of those things are fragmented into small pieces. Maybe that will equalize and maybe we’ll get a pushback. I think people will use tweets to find things which are larger. There will be a balance. I think serious pieces of work will be important. There will be a range of all those things.

It may involve new protocols. We are looking at new payment protocols.

One of the solutions may be to get payment protocols on the web, new payment protocols, so it’s easy for me, as I read your blog, or as I read your journal, the output of your journalism, I might be able to tell my browser, “You know what? Whenever I really enjoy an article, I’m going to hit this button, and I want to pay the guy who wrote it, and I want to pay the guy who pointed me at it,” because I really appreciate that.

…It’s building new systems. There will be new genres, both of works and of journalism. They won’t all be paid for by payrolls. They won’t all be paid for by advertising. We’ll have new types of products, ways of paying for them.

We just have to be creative. You think about how the user, what user interface would you like to have that makes it easy to pay for something, to give credit where credit is due? Let’s see how we can implement it.

Without the middleman, without having to cut down the trees and make wood and the paper and so on, then I think maybe we’ll be able to solve both of these problems.

We also spoke to Julius Genachowski, who in April of 2013 resigned as Chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, after presiding over a tumultuous period in the government oversight of communications and electronic media industries. He shares a sympathetic concern.

…I commissioned a report on the information needs of communities in the digital age. By commissioned, I mean we put together a team here at the FCC and brought in a terrific former journalist and former Internet entrepreneur named Steve Waldman to run this effort. And he produced his report, at this point, about two years ago. It’s called the “FCC’s Report on the Information Needs of Communities.”

And it concluded some worrisome things….

Let me describe the report a little bit…. It found that there were both opportunities and challenges, and then it tried to be concrete about what the challenges are. On the opportunities side — let me start there before we get to the challenges — new communications technologies, the Internet, mobile, are creating new distribution channels for news and information at much lower costs of distribution. You or I could start a news and information business tomorrow on the Internet at a much lower cost than if we wanted to do exactly the same thing 20 years ago and we needed to launch a newspaper or TV station. This is a general fact about the Internet and opportunities for new businesses. The cost to get started and the barriers to entry are a lot lower, particularly in a world where we preserve a free and open Internet.

In fact, there are lots of examples of online entrepreneurs that have started news and information businesses. But the report also found that, when it comes to news in particular, while the distribution costs may be a lot less than they are historically, it still costs money to report the news. Reporters don’t work for free, nor should they. The business models to generate revenue to pay for reporters, even on the Internet, are not where they need to be to support a robust reporting operation.

The report found a few different things. I think it tried to be intelligently nuanced. It identified the largest challenge around local news and information as opposed to national news and information. Local journalism, covering the mayor’s office, the governor, state, city, local agencies, that’s where we’ve seen the greatest cutbacks and the hardest economic challenges, as compared to national news. That doesn’t mean there aren’t issues there, but there continues to be vibrant coverage of Washington.

Local news and information, particularly in the area of accountability journalism, is where the report found the biggest challenge. The report drew a distinction that others have drawn, but it’s important to keep in mind, between opinion and journalism. The Internet is great to facilitate the wide distribution of many different opinions. It’s much harder when it comes to building a reporting entity, particularly if what you’re trying to do is build reporting teams in lots of different local communities.

…I just want to make sure that I’m following you; that I think you would agree that that part of the puzzle’s not been figured out. That has to happen and that path is really unclear.

I completely agree that it hasn’t happened and that the challenges are very significant. But I would also argue that there’s tremendous value in local accountability journalism. People really want to get local accountability journalism about their communities, about things that really matter to their lives. My hope is that innovators in this realm will continue to mine it. I don’t know if they’ll be existing companies that figure it out or whether they’ll be start ups, but I don’t think we’re talking about trying to figure out a business model to give people broccoli that they don’t want. I believe that people really want local accountability journalism because they care about their home, they care about their kids, they care about their lives and they want to be engaged citizens. Someone will figure out how to provide that and build a business model around it.

And from the person who many now view as the keeper of the last flame, a clear, unvarnished statement of purpose.

[To Arthur Sulzberger:] But the assumption over time is that people are going to continue to appreciate quality journalism. Without that, there’s really no…

If that goes away, then you’re right. Our mission is gone, because that is our mission.

Sulzberger isn’t the only person in the industry with a surname that’s synonymous with the long history of journalism in the U.S. But in this next case, the namesake also has backed some of the savviest new ventures in digital communications.

What has changed in the media equation is the mass media equation. Newspapers in 2013 are not mass media anymore.

The Economist can survive. The New York Times can survive. Newsletters can survive, even have circulation revenue. The idea that the mass market is a newspaper market or even a publishing market, I think, is in great danger.

And from yet another member of a storied news family, a few months before he announced the decision to sell his historic newspaper, a sense of uncertainty that perhaps foretold his decision to exit the business.

One of the questions that faces places like The Times and The Post, but I want to come back to local newspapers broadly, is…there any kind of a plus to a news organization in having really high-quality reporting and editing? I’m pretty sure the answer to that is yes, but we have not figured it out.

From a new-generation news entrepreneur, we heard a call for a bit more patience, some time to find new models that work.

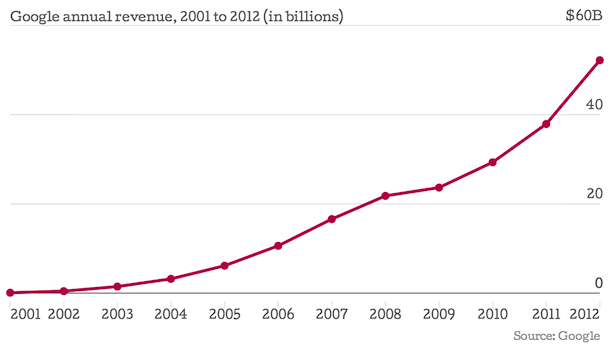

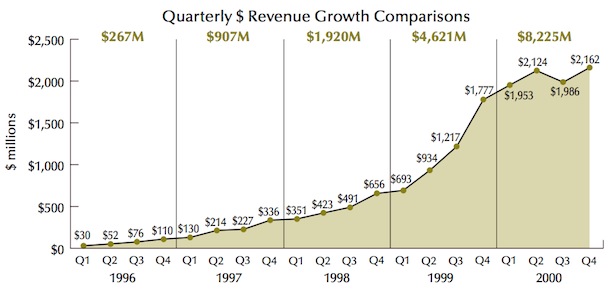

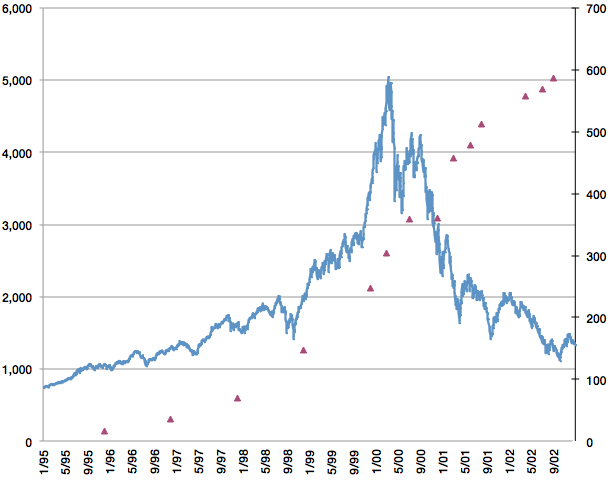

One of our goals at BuzzFeed is to build a real, sustainable business that generates profits, to build a media company for the social age. There are all these big media companies that, 10 years ago — Time Inc., The New York Times — all these companies were worth $10 billion and were seen as really great businesses. But you haven’t really seen that with digital yet. You’ve seen people build companies that, by old media standards, are fairly modest. I think that’s because we’re at the beginning of a transitional period and that eventually it should be possible to build much larger, more successful, more profitable companies in the digital space.

To the extent that news remains advertiser-supported, a different kind of church/state relationship may be evolving — one where the boundaries may not be as clear.

Interestingly, talking to newspaper owners currently, if they say to you, “What can we do that would help WPP, or GroupM, or Mindshare or whatever it turns out to be?” It’s always that we say, “Greater flexibility.” And by the way, this boundary between advertising and content—advertorial, right—is going to get increasingly blurred. I mean, I don’t think that consumers should be misled. If it’s an advertorial it should clearly say at the top of the page, “This is an advertorial.” But content. There’s going to be increasing amounts of sponsored content — of content that’s developed for specific commercial purposes, just as much as for editorial purposes — and the two things are going to mix.

We also heard advice about where not to be in the future of news from someone who’s been in print, some of the earliest web publishing efforts, the heart of the most successful online advertising business, and now leading an effort to reinvigorate an old digital brand.

…The overall thing, across the entire Internet right now, regardless of what content space you’re in is, don’t get caught in the middle. If you go back to the Andy Warhol statement of people care about high-end luxury and they care what happens on the street. Anything else in between comes across as mediocre to consumers. That’s where the Internet is on local today. You either should be national, New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Huffington Post, or you should be hyper local and mean something to consumers. Our investment, we call it the bar bell investments, tend to be at both sides of those bar bells.

And we got a strong reminder from another player on the digital side, a reminder for newsrooms not to try to compete with technology on its terms.

The benefit that the journalists have over the technologists is their ability to do these in-depth, content-rich analyses and essays around things. Instead, they’ve tried to optimize, in many cases, for, “We have to be the fastest and the first and the best distributors.” But the technology’s always going to be the fastest and the first and the best distributors. The technologists are going to be particularly bad at the in-depth analysis and the content and the thoughtful reporting….There haven’t been enough attempts to monetize that as opposed to trying to compete with the technologists at being fast.

And from the journalist-turned-Silicon-Valley-all-star, a reminder that if you’re not unique, you’re in trouble.

I think, on the whole, that media and forms of journalism that have something original to say, have their own content, have stuff that’s really proprietary and have their own voice, as opposed to distributing the wire services or being warmed-over versions of stuff that you can find all over the place — I actually happen to think that they have a far brighter and better future than they ever did.

…Most of the existing media companies who don’t have their own content will go the way of the dodo. No doubt about that. There will be a few that are able to engineer a leap over this gulf. But we all know the industries where the makers of horse carts or locomotives weren’t the leaders in the next form of transportation. It’s no different in the media business.

And there was plenty of handwringing, especially from people who have had to fight the continuous battle of trying to produce quality journalism with ever-dwindling financial resources — only to have the ultimate product benefit the low-cost competition.

Talk about that context of the [investigation into the Catholic] priest scandal that you led at The [Boston] Globe.

Shortly after I got there, we embarked on a series investigating the Catholic Church. The issue there was not just whether a priest had abused children, which there had been cases of that before, but whether there had been a pattern of abuse and that the church knew about that abuse and then reassigned priests to other parishes where they then abused again, and whether that pattern had taken place over a long period of time. In fact, it had in the case of dozens and dozens of priests over decades.

Now, that was not something that anybody was going to tweet about. The priest abusers weren’t going to tweet about it. The victims weren’t tweeting about the abuse that had taken place. The Church wasn’t tweeting about it. Nobody was tweeting about that. That kind of information would never have been known had it not been for The Boston Globe doing that expose.

But, from the other side — playing a web-only hand — there’s a more sanguine view being expressed.

[To Henry Blodget:] The chest beating…on how do we support serious stuff? …Does that scale support a Baghdad bureau? Does that support the things that people worry are going to get lost in this transition?

Without question, or it supports what the Baghdad bureau is turning up. Twitter, Facebook, and blogs, just an incredible new mechanism for unlocking information. We see that all the time. You can do things. You do not have to have a reporter on the ground, necessarily, to learn a huge amount about what’s going on. Citizens are contributing to global knowledge.

I don’t know whether it’s going to make sense for The New York Times to have a Baghdad bureau. What I’m very confident about is that the world will continue to be vastly better informed than it ever has been before.

I think even with the pressure on newspapers, the world is vastly better informed than it ever has been. We’re going to digital.

…I think the hand wringing is completely misplaced.

Before the digital wave came along, plenty of news businesses were almost as much about conveying social status to their owners as they were about delivering those large profit margins (we said “almost”). Think Bill Paley at CBS or Henry Luce at Time or Kay Graham at The Post. Through the course of our conversations, there were a few who suggested it will fall to the rich and powerful to fund journalism because they think it’s important or maybe just for the influence. Not surprisingly, one name that always comes up in that category is Eric Schmidt.

[To Eric Schmidt:] Can you take off your Google hat for just a moment…? You’re a very wealthy, very powerful man who’s shown a lot of intellectual interest in politics and journalism. You’re close to people like Steve Coll, who’s now in a position to do something really good for journalism and journalistic education [as the new dean at the School of Journalism at Columbia University] and bring it into the future. We’ve seen some non-economic models out there, like the Sandlers… [Herb and Marion, who funded the not-for-profit investigative effort] ProPublica. We’ve seen Mike Bloomberg who, for whatever reason, is willing to have a $500 million news organization attached to a proprietary data business…. Do you favor, personally, Eric Schmidt, the idea of wealthy, powerful, interested people getting involved in non-economic models to fund quality journalism in the interest of democracy?

I’m always in favor of more journalism and in particular, more investigative journalism done by the kind of quality that we’ve been losing. My personal favorite is the situation where you’ve got a business that throws off enough cash that that cash can then be used to do non-economic things. The reason is that that’s an industrially stable structure for a long time. With individuals, the problem is they run out of money or they change their minds.

So that could be a Bloomberg then?

For example, the Bloomberg model is a very good one. I’m very impressed and proud of Mike for doing that. There should be more of that. If you go back to The Washington Post, The Washington Post is tied to an education company [Kaplan].

(But, of course, with the sale of its namesake newspaper to Bezos, what remains of The Washington Post Co. is an education and television station company — no longer one with a major stake in the news business.)

With no hint that a check to save journalism would be forthcoming from the Googleplex, we turned to another wealthy capitalist who entered the media arena, only to be surprised by his argument that market forces must pertain.

I think you could make an argument that rich people are a real danger to journalism, maybe not in the moment but over the longer term. To answer your question directly…I meant to say both things. Deeply unsatisfying, to me, to keep putting out something that was failing against any commercial standard. But I also don’t think it’s a healthy thing for the enterprise. You end up with two bad things going on. One bad thing is that it can never grow. No matter how wealthy the fund is or the person is that’s going to subsidize it, there’s going to be a finite amount of money in the trust. It’s going to produce a finite amount of income. You end up creating an enterprise that operates at that level, and then the next year, when things cost more, it will operate at that level but a little more tightly squeezed and the next year a little more tightly squeezed.

We saw that with The Atlantic, with [owner Mort] Zuckerman. He was genuinely generous with the enterprise, but he had a limit of how much he was going to spend on it, which was about $4 million in a bad year. The Christmas party had become a potluck supper, where everybody brings his own. They had not been able to afford the high-end writers. They had lost people like…Nick Lemann had moved on when the contract wasn’t competitive enough. They were increasingly publishing the works of academics who didn’t charge for the pieces or charged at a lower per-word rate.

One thing you end up with is a ceiling on the growth and a meaner and meaner culture. “Meaner” in the sense of tighter, financially. The other thing that happens is, they get whimsical and quirky. Since there’s no external standard to which you have to perform, you can publish whatever you want. You can report whatever you want. You can do the indulgences of the aggregate of your talent base.

There’s something really good about The New York Times waking up in the morning, going, “We’re not breaking the news we used to break. We’re being scooped by these people. Furthermore, we’re losing this talent. Everybody meet in the conference room at 8:15 because we have to figure out what we’re going to do.” Those kind of crisis moments which the for-profit sector forces on you relentlessly.

Perhaps surprisingly, one of the most optimistic views of the future of journalism comes from inside Google’s own news operation:

As I’ve frequently said, I’m very optimistic about the future of news. I’m extraordinarily optimistic about the future of news, but it’s going to be a very, very different landscape. The reason I’m optimistic is because we have these huge open systems. The simple fact that in effect, we put a printing press in everyone’s hands. That’s a hugely powerful thing. You’ve got a lot more people participating in the dialogue than ever before. Doesn’t mean that it’s all good content. It’s not. Obviously not. Still wheat-to-chaff ratios. But a lot of it is very good. You’ve got a very open system. You also have opportunities, but it does require, as I said, us, when we look at the future of journalism, to rethink all the models, to rethink what is the right way to build a news product in this realm. How do you build audience in this realm? What are the right uses of the media form? What are the right uses of computational journalism? I think computational journalism has extraordinary potential that has not really been fully explored.

And maybe just to succumb to that natural desire to end on a high note — we turned to one of America’s most buoyant multi-media public intellectuals.

I think it will be worked out. People are always worrying about something. The Baghdad bureau, well then on the other hand, they’ll say there won’t be local news. Someone is worrying that the Internet will drive away every part of the current media. There isn’t anything that someone doesn’t have a theory needs to be subsidized. I think it’ll all work out. My friend Nick Lemann, who just retired as dean of the journalism school [at] Columbia [University], says whenever he has these discussions — and in his 10 years there he’s had plenty — he says the one thing you’re not allowed to say in these discussions is, “It’ll all work out somehow.” But I believe that.

That sounds a lot like something your mom might tell you right after you didn’t get the part in the school play. And maybe we believe that too, really. It might just all work out somehow. But that’s for the news, the journalism, the public good. That part might just all work out somehow, eventually. In the mean time, the transition from what’s left of the old legacy news business to whatever comes next is likely to be the swiftest undertow yet of the digital riptide. The next full moon, the next hurricane, the next digital media breakthrough — seems bound to take down a lot of familiar swimmers before it all works out somehow.

Recent Comments